Kristina Campbell is a freelance science writer and content marketer who creates quality blog content on digestive health for Canadian pharmacies

Photo Credit: by Kristina C.

Anxiety accompanies a tense conversation, anger accompanies a social snub. You pin your emotional reactions to things that happen in the outside world. But even as you walk away with teeth clenched, is there ever a tiny part of you that wishes you could have been more chilled out about the situation?

Scientists are trying to figure out if there’s a way to hack our brains to make them more resilient to extremes of emotion, and to make us feel positive emotions more often. In the past decade we’ve seen huge advances in our understanding of the gut microbiota – the trillions of friendly, live microorganisms that live in the human digestive tract. It turns out the microbiota might be key players in the constant communication that happens between the gut and the brain, and that this communication might impact our emotional reactions.

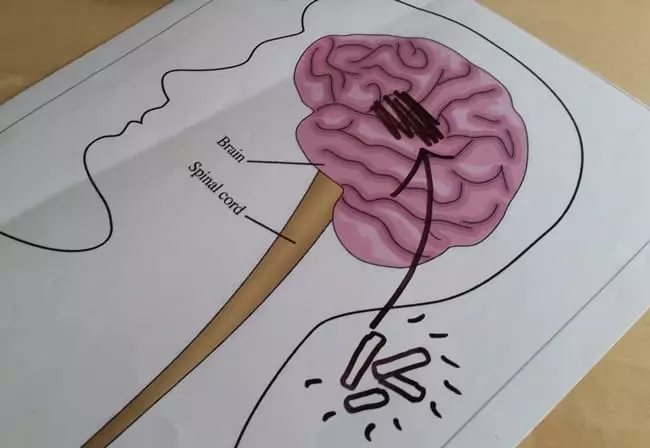

How could gut-brain communication happen, though? There’s a kind of superhighway spanning the distance between the digestive tract and the brain. It’s called the vagus nerve, and it transmits electric impulses along its fibers between the colon and the brainstem, with links to other body parts, too. Microbes are able to activate these nerve impulses, and this could potentially be one of the ways they affect human emotions.

Research on humans is limited, but there's some evidence that changing gut bacteria can make you mellow out in the normal course of life. In one study, researchers gave healthy women a fermented (probiotic) milk product twice a day for four weeks. As observed through functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), their brains showed positive changes in the activity of regions that handle emotion and sensation. Another study showed “beneficial psychological effects" of a probiotic supplement containing two species of bacteria. And a survey of young adults found that consuming more fermented foods like miso and traditional sauerkraut (which normally contain live bacteria) was associated with lower levels of social anxiety.

These studies are like dots far apart on a map: they all lend support to the idea that probiotic bacteria can help stabilize emotions, but it’s hard to draw a connection between them that would make a real difference to human health. It’s notoriously difficult to study emotions in humans, since you can measure them in so many different ways: from brain imaging or wellbeing questionnaires, to nail-biting behavior or the number of party invitations you decline. And even if scientists could be sure their measurements were valid, they would struggle to know exactly which strains of bacteria in which doses were responsible for the emotional improvements.

Now consider those with more serious mood challenges, such as depression. Scientists have found that the bacterial community that lives inside the gut of someone with depression is, on average, different from the one that lives inside a healthy person. The bacterial communities in people with schizophrenia, autism, some forms of anxiety, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease are all different from those in healthy individuals, too.

But just because two things occur together doesn't mean that one causes the other. You tend to see rain and umbrellas together, for instance, and you tend to see certain gut bacteria in individuals with autism. But this doesn't mean the gut microbiota cause autism any more than umbrellas cause rain. And we have next to no reliable information when it comes to how you can change the gut microbiota in people with these diagnosed conditions.

When it comes to mice, researchers are indeed making progress in changing the gut environment to change behaviors that may be linked to emotions. To simulate a psychological disorder, scientists often use mice that experience separation from their mothers after birth. These mice benefit from probiotics in some studies: the friendly bacteria help reduce their anxiety- and depression-related behavior, like becoming immobile instead of trying to swim their way out of a glass cylinder filled with water.

The problem here is that mouse emotions are very different from human emotions. You can make a mouse swim for its life and you can be pretty sure it’s going to experience something like what we call ‘anxiety’, but there’s no way to ask how it’s feeling. What really matters is whether scientists can successfully change the gut bacteria of humans in a way that has a measurable effect on a mental illness. There are many questions to be answered before we achieve this goal: Which bacterial species have the strongest impact? Is it different for every person? Does it matter how often you ingest the bacteria?

Perhaps in the future you’ll be able to eat a container of pre-argument yogurt to fortify you against the strong negative emotions that you expect to arise. Or even take a bacterial cocktail to bring you out of the depths of a serious depression. But we’re not there yet. Time will tell whether we can really get a handle on emotions through the activities of the gut microbiota.

###

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *.